In July 2024, researchers released ten rehabilitated juvenile loggerheads into the Bay of Biscay, equipped with miniaturized satellite tags to track their movements. One turtle was tracked for longer than a full year, setting a record for turtles of its size. Led by Upwell, Aquarium La Rochelle, and Mercator Ocean International, the project is revealing new insights into the little-known early years of sea turtles.

Juvenile Turtles in the Bay of Biscay: From Rescue to Tracking

In July 2024, ten young loggerhead turtles left the care of the Study and Care Centre for Marine Turtles (CESTM in French) of Aquarium La Rochelle and were returned to the open sea in the Bay Of Biscay. Each turtle was equipped with a miniaturized satellite tag, no bigger than a coin, to track their movements. One of the sea turtles, named Charles Darwin by the researchers, would go on to make history by transmitting a full year of tracking data, the longest record ever for a turtle of its size (about 15-20 centimetres).

This release was part of the Lost Years Initiative, a global collaborative programme led by the American NGO Upwell. The initiative involves organisations from many regions of the world, including Japan, South Africa, Thailand and the Azores, with CESTM and Mercator Ocean International as key partners in France. The programme aims to shed light on the ‘lost years’ of sea turtles: the poorly observed period between a hatchling’s departure from its natal beach and its return to coastal areas as adult or subadult to forage or reproduce. During these early years, turtles are brought by Ocean currents while seeking food and suitable water temperature, and avoiding predators, carrying out movements and migrations which have been, until recently, almost impossible to track.

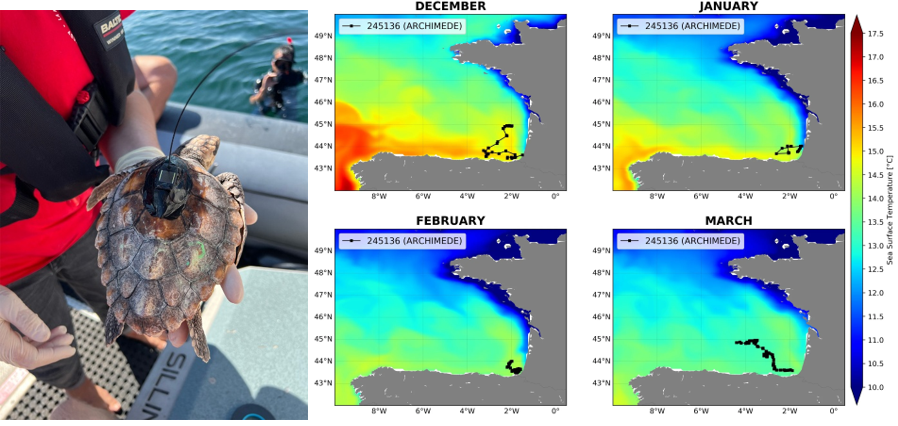

The Bay of Biscay, where the rehabilitated turtles were released, provides an example of the challenges young turtles face. This bay is a highly productive area throughout the year, with rivers bringing in nutrients that sustain abundant marine life and provide rich foraging opportunities for young sea turtles. While in summer mild water temperatures characterise the area, in winter, sea water temperatures can drop to 10°C, which leaves the turtles “cold-stunned”, a life-threatening state in which they lose mobility and risk stranding on shore. CESTM’s rescue and rehabilitation work gives these turtles a second chance, and the installation of satellite tags, safely attached on their carapace before release, turn their journeys into valuable scientific data.

The tags, specifically designed to be lightweight and robust, transmit the turtle’s position to the researchers whenever it reaches the sea surface, allowing scientists to follow specimens for several months. Every new data point contributes to a deeper understanding of the young turtles’ lost years at sea. This knowledge, in turn, supports more targeted and effective conservation strategies.

Figure 2. After installing the small satellite trackers on their shell (left), the juvenile sea turtles are released in the Ocean (right). Credit: Aquarium La Rochelle.

Insights from One Year of Juvenile Turtle Tracking

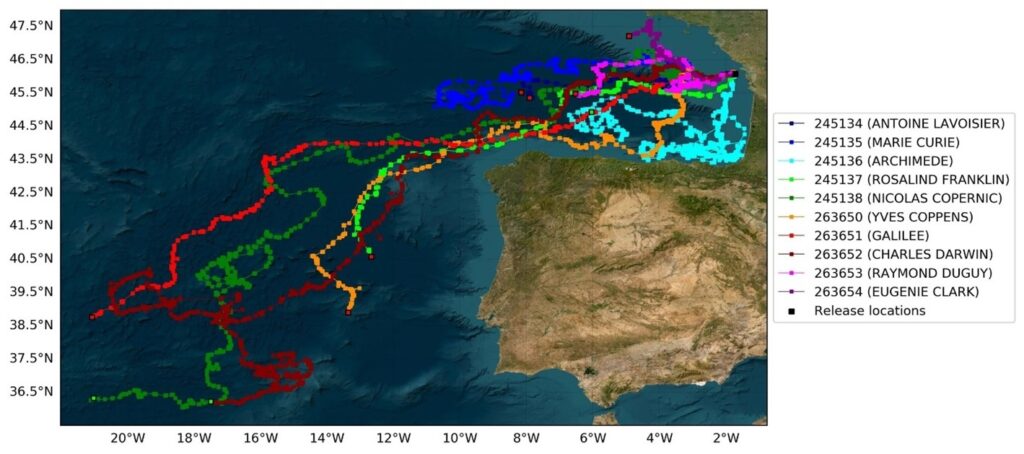

The ten turtles released in 2024 took markedly different paths. Some turtles, including Nicolas Copernic, Charles Darwin, and Galilée, headed south into the open North Atlantic, some reaching areas between mainland Portugal and the Azores and passing through regions frequented by fishing vessels and maritime traffic. On the other hand, Archimède remained within the Bay of Biscay, moving mainly along the Spanish shelf where waters were slightly warmer.

Some of the turtles were also equipped with instruments measuring the depths of their location, providing additional insights into their behaviour. Most of the tracked turtles stayed near the surface, within the top five metres of the water column, with occasional deeper dives.

Although Archimède’s data provides information on only one specimen and cannot be representative of its whole species, its trajectory introduces new key insights on how a juvenile turtle interacts with its environment for extended periods of time and changing oceanic conditions.

For scientists, such extended records help answer questions about whether the Bay of Biscay serves as a year-round habitat, a seasonal refuge, or a location which can become unfavourable under certain conditions. These records also give numerical models better data to compare with forecasts, ultimately improving the ability to predict juvenile turtle behaviour in different oceanic conditions.

Linking Sea Turtle Tracking to Oceanographic Insights: the role of Mercator Ocean International

However, location data alone cannot explain why turtles choose certain routes or areas. To answer those questions, researchers placed each position within a detailed reconstruction of the Ocean state at the precise time and location of each transmission, combining information on temperature, sea surface height, and bathymetry. Mercator Ocean International provides these Ocean analyses and forecast data, which are integrated with the tracking data collected from the sea turtles. This combined approach makes it possible to explore how currents might influence turtle movement, how temperature shapes their distribution, and where productive waters might provide feeding opportunities. The same datasets can also highlight areas where turtles’ paths intersect with human activities.

By bringing together CESTM’s rehabilitation work, Upwell’s tagging expertise, and Mercator Ocean International’s Ocean data, the project directly connects rescue operations with scientific research and informs conservation planning.

Mercator Ocean International has conducted and contributed to multiple studies combining satellite tracking and oceanographic modelling, including recent work revealing the swimming activity of juvenile Pacific loggerhead turtles. These studies have contributed to significant insights into the lost years of sea turtles.

What’s next

On 30 June 2025, work continued with a new group of nine rehabilitated juvenile loggerheads released at La Rochelle. Each turtle is equipped with a microsatellite tag. The data collected will improve the ability to identify patterns in seasonal migrations, preferred habitats, and potential exposure to human-related risks.

By continuing to integrate Mercator Ocean International’s Ocean analysis and forecasting capabilities with satellite tracking, the initiative turns each turtle’s journey into a valuable dataset which can inform predictive models of juvenile movement. These models provide actionable knowledge for science-based marine conservation planning. As the newly released turtles begin their migration, the partnership between Upwell, Aquarium La Rochelle, and Mercator Ocean International ensures that their tracking contributes to a clearer picture of turtle lost years and the dynamic environments which influence them.

Additional Resources

- Read more about the ‘Lost Years’ project: https://www.upwell.org/unraveling-the-mysteries-of-the-lost-years

- Get insights into the results after one year of tracking: https://www.upwell.org/news/2025/6/6/loggerheads-in-the-bay-of-biscay-and-beyond

- Access the full paper on how microsatellite tags contribute to the understanding of turtles’ ‘Lost Years’, led by Tony Candela and published on Animals: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/14/6/903